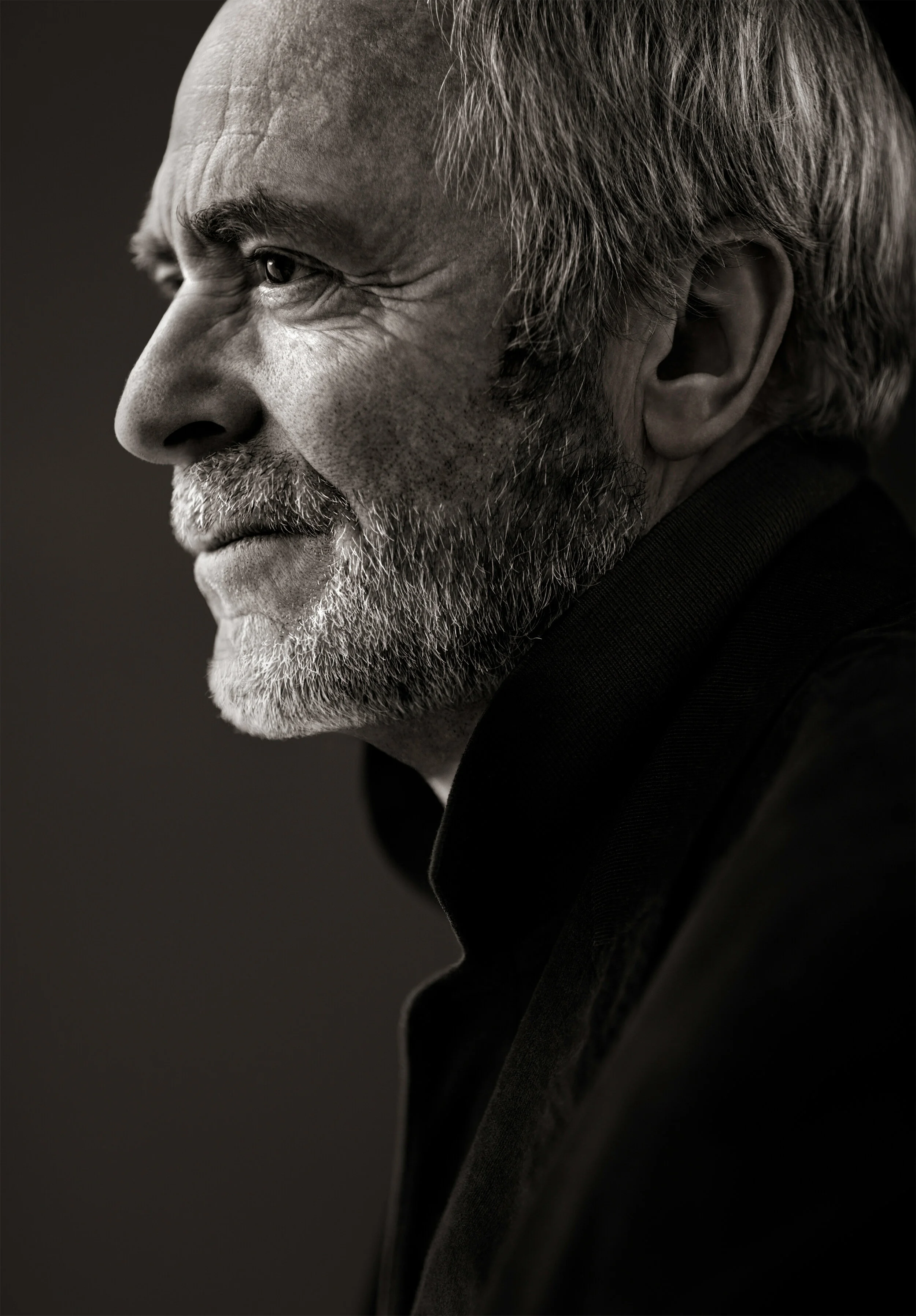

BIO

Known for his stark, honest portraits of the most famous and infamous faces from the worlds of entertainment, art, sport and music, Greg Gorman’s images have intrigued the viewer from the onset of his career. Over the years Greg has been acknowledged for his contribution to the world of photography, most recently being recognized by The Professional Photographers of America (Lifetime Achievement Award in Portraiture) as well as The Lucie Awards for Portraiture. His charitable works by such organizations as The Elton John Aids Foundation, The Oscar de La Hoya Foundation and Paws LA to name but a few have also been critically recognized.Besides traveling the world for specialized photographic projects, Greg continues to work on compilations of his imagery and exhibits his work at galleries and museums around the globe.

It's Not About Me-A Retrospective marks Mr. Gorman’s twelfth monograph. As well, Gorman is one of the most sought after speakers in the photographic community and shares his expertise in hands-on photographic workshops worldwide. Greg’s latest career venture has been in the world of wine-making. In collaboration with Dave Phinney of Orin Swift Cellars of the Napa Valley, Greg began making wine under his own label, GKG Cellars, in 2006, receiving high scores from both Robert Parker and the Wine Spectator.

Born in 1949 in Kansas City, Missouri, Greg attended the University of Kansas with a major in Photojournalism and completed his studies at the University of Southern California, graduating with a Master of Fine Arts degree in Cinematography. Greg resides with his two French Bulldogs in Los Angeles, California and spends his spare time fishing. <www.gormanphotography.com>

Gorman is represented worldwide by the Fahey Klein Gallery, LA at contact@faheykleingallery.com. In Canada, Gorman is represented by Izzy Gallery at izzygallery@gmail.com (phone +1.416.8317799).I T ’ S A L L A B O U T M E

It all began when I asked my fishing buddy, Buzz Gher, if I could borrow his Honeywell Pentax camera to photograph Jimi Hendrix in concert in Kansas City in 1968. He readily agreed and advised that I shoot Tri-X film at 1/60th of a second at f /5.6. He was pretty sure I would capture an image in doing so. The following morning, I went over to his home and we processed the film in his darkroom in the basement of his parents’ home. Afterward, we decided to make some silver prints, and when I saw that first image appear on a white sheet of paper, I was hooked! I wasn’t quite sure if the photograph was soft because I had smoked too much dope that night (it was the hippie era!) or if the slow shutter speed was the real culprit.

Nonetheless, the entire process intrigued me to the degree that I wanted to explore all of this with a real photography course the following spring at the University of Kansas, where I was in my second semester of a Liberal Arts and Sciences degree in the William Allen White School of Journalism. The only photography course being taught at the time was one in photojournalism, which I decided to take. Try as I did, I couldn’t shoot anything that couldn’t talk back to me (with the exclusion of a doll I found on an isolated farm road in Lawrence, Kansas). I realized at the start that people were my one and only interest.

From the beginning, music was the driving force behind my keen interest in photography. School weekends were often spent in Kansas City shooting local rock concerts for a radical newspaper aptly called Reconstruction.

Early on, one of the people who influenced me most was the late Elgin Smith. He had his own photography business and processing lab in Kansas City, and I enjoyed hanging out with him. I had met Elgin several years earlier when I was selling Fuller Brush Co. door-to-door. I told him of my interest in photography and he took me under his wing and gave me my very first show in Kansas City at a PPA event (Professional Photographers of America). The exhibition was of photographs I had taken in 1968 in

Washington, D.C., during the march on the South Vietnamese Embassy. It was during this exhibition that I met Larry Stevenson, who worked for Eastman Kodak and seemed taken by my imagery. He offered to let me use his color darkroom on the weekends to print. I would go over to Larry’s home around six in the evening and emerge around six the following morning, having printed all night long. I was becoming more enthralled with the art of photography and image capture. It was at this time that Larry advised me that if I had a real interest in photography, I needed to go to film school. Otherwise, according to Larry, I risked becoming a lab technician of sorts—something that held little interest for me.

With this in the back of my mind, I began researching film schools and decided to check out UCLA and USC since my father was living in California. That same weekend, I was asked to photograph a Byrds concert at a local high school in Kansas City. After the show, in the dressing room, I struck up a conversation with their drummer, Gene Parsons. He asked me what my intentions were after finishing school. I quickly told him I was thinking of moving to California and becoming a professional photographer. Gene graciously offered up his personal information in case he could be of help once I made the move.

Little did I realize at the time how that information would become extremely helpful to me as a struggling artist. After the move to Hollywood, I was battling to make ends meet—spending my days routinely delivering photographic supplies in East LA to graphic arts houses in a two-ton van! The Byrds were getting ready to leave on a three-month tour for their highly successful album, Untitled, produced by Terry Melcher. Gene was quick to offer up his home to me while they were on tour. Their three-month stint abroad, which meant free rent for me, certainly helped me land on my feet. To this day, Gene remains a very good friend for whom I will always owe my gratitude.

When I finished college at USC with an MFA in cinematography, I was once again, like most college students, a bit disoriented and lost! I was shooting headshots for would-be actors and actresses for $35 a day including film and processing. I bulk-loaded reusable film cassettes and processed and printed everything in my single apartment’s kitchen-turned- darkroom in Hollywood near the Magic Castle. My rate quickly went up to $75 (LOL), which I thought was great! I was actually making some sort of a living taking pictures of people. At the same time, a dear friend, Dave Fulton, who was working in the produce industry, offered me work photographing for his publication to give me some extra income. The work was easy but didn’t hold much interest for me, as it continued to be the interaction while shooting people that kept me going. I realized that my passion for taking photographs was more about the people in front of my lens, and that although I was happy with my film degree, it really was the personal interaction and the one-on-one communication that drove my photographic interests.

My next adventure (1974–1977) was as an art director and designer for a company in Beverly Hills run by the late and well known film producer, Arnold Kopelson. At the time, Kopelson had a company called Inter-Ocean Films, which branded and packaged television and independent films for foreign sales. I created scores of posters and press books for Kopelson. During this period, I also worked alongside producer Wendell Niles documenting the pro-celebrity tennis circuit and organizing the tours. The support of Kopelson and Niles, along with the work that I did at the time, opened doors for me into the film world.

As my images began to appear in some local music publications in Los Angeles, I was contacted by the late Barbara DeWitt (Bruce Weber’s sister) and asked to shoot David Bowie. This was a big break for me. No matter how talented an artist may be, it boils down to “Who have you shot?” Having an artist like David Bowie in my corner certainly added credence to my early career! Barbara was instrumental in helping

launch my career with artists like Bowie, Frank Zappa, and Iggy Pop—all cutting-edge artists.

At about the same time, I started working on feature films as a special photographer shooting the star talent. However, once again it wasn’t until Barbra Streisand called me out of the blue, introducing herself, that I gained another measure of credibility.

Barbra told me that she understood I was the special photographer on the film she was about to star in. She wanted to know what my plans were in terms of how I would photograph her. We discussed some ideas and ended up having a terrific relationship on the film, which led to many more projects together.

Following Barbra, I was fortunate to photograph key art for Tootsie, The Big Chill, and Scarface—all within the same time frame. Everything happened so fast, I just rolled with it!

In the ensuing years I was also lucky to work on many motion picture campaigns. The images in these campaigns went relatively unrecognized outside the industry, since there were rarely, if ever, photo credits given for work commissioned by the studios.

In 1982, as a special photographer on the film Grease 2, I had the opportunity to work with a young Maxwell Caulfield. He had just come from a stunningly successful run off Broadway at the Cherry Lane Theatre in Entertaining Mr. Sloan. Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine was very keen to have him for the cover of their publication. I had the access to Maxwell and I got the call to photograph him. This was a very lucky break for me, as Interview magazine was very well regarded in terms of content and imagery. Warhol’s magazine was a terrific outlet for my editorial exposure.

Looking back, I see how much has changed. Today it would be virtually impossible to capture all the shots I was so fortunate to take back then. The star system has become too insular, with publicists, agents, managers, and even personal assistants dictating the protocol their talent will agree to before going forward with any form of a photo session. All this structure has certainly killed one’s enthusiasm and drive today!

In 1983, a small emerging eyewear company on Melrose Avenue in Hollywood asked if I’d be interested in shooting a celebrity-driven campaign for them. This campaign was imagined by the creative team of Jeff Gorman and Gary Johns. I had access to the talent and the chutzpah to convince them to shoot for a song and a dance. Back in those days, the talent wasn’t as aware of the value of their testimonials. In fact, Andy Warhol himself called to ask me if he could be in one of the l.a.Eyeworks ads, which appeared monthly in his magazine.

Between Interview magazine and the l.a.Eyeworks campaign, my style and voice as a photographer emerged. It is such a funny thing—finding one’s voice and style. It changes over time, and almost without realizing it, one develops a new way of looking at things. I remember from my early days, I had all of my photographs blown up big and tacked up on the walls of my first studio, located above my lab, Photo Impact. Looking back, everything seems so over-lit, and the photographs look like interchangeable postage stamps with far too much hair-light and shadow detail. Shadows should frame a face—not expose it! Everyone looked good, but little was left to the imagination! The pictures answered too manyquestions. I began to realize the importance of one thing—that it wasn’t what you said in the highlights that mattered, but what you didn’t say

in the shadows that kept people coming back, wanting to know more. The intrigue of the unknown—isn’t that what drives most people?

Creating a dynamic range between highlights and shadows became my signature mark. Much of what I learned about directional lighting came from discussions with my first assistant, David Jacobson. I also continued to study more intensely the work of the portrait photographers I admired—at that time my biggest influences were George Hurrell, Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, and Helmut Newton.

There’s nothing really fancy, tricky or gimmicky about my approach. It has always been very straightforward portraiture. Probably too straightforward for some in today’s world. But for me, it’s always been about trying to get at the heart of the matter—the human psyche. Personality portraiture is just that. Trying to meet subjects on their level and winning their trust and confidence. I want people to feel like I am

playing for their team—not playing for some art director or client whose agenda may put the talent in an awkward or uncomfortable situation. I have seen how this can alienate everyone on the set!

Over the course of my career I did very little editorial because my reputation was one of siding with my subjects, not the clients. This was what won me the ability to accomplish the job and get the necessary imagery—not to mention how it helped in creating many long-standing relationships with the talent themselves! Trust and confidence! Not, perhaps, what magazines wanted to pay me for. They wanted that

vulnerable askew moment. I always felt the personal time spent with my subject for a magazine spread was a mutual and shared effort and belonged to us. We were not there to please the likes of an editor who cared more about their own personal ego than the talent.

In today’s world, portraiture photography seems so different than the world I knew as a young photographer. The styles have changed. Everything is more editorial or overworked, with excessive Photoshop as an example. It seems there is very little honest portraiture today. Today it’s about a gimmick, a trick, or simply a celebrity’s “selfie” taking center stage over a classic portrait focusing on the features of the talent in front of the camera. Creating an image that will stand the test of time is what appeals to me.

I remember one day my longtime agent telling me that I needed to reinvent myself if I wanted to stay in the current marketplace. I thought to myself that I had just spent the better part of my career defining my style. Why the hell would I want to go out and change that at this point? Why confuse the issue?

It has been an interesting journey reviewing 160 large boxes of transparencies and negatives from a time frame spanning fifty years, trying to determine what is honestly relevant or not—which images should be included and which ones are not worthy of sharing in a retrospective? Not an easy endeavor.

As a photographer, being a visual chronicler, one does not always agree with the politics of one’s subjects. The history of the subject doesn’t make the imagery any less important. I don’t believe in any form of censorship and consequently left that element out of my selection process.

There were things that did influence my selection process, however. Sometimes it was the lighting that embarrassed me. Often times I wondered why I compromised my style and gave in to a less dramatic lighting approach and missed the opportunity of creating an interesting and compelling portrait of an important talent. Believe me, this upset me on many an occasion—realizing I was not being true to myself as an artist was painful. I wasn’t practicing what I preached in my workshops!

Not surprisingly, my photographic style has evolved over the years. Sometimes the photographs look dated and I struggled whether to include them in this book. On the other hand, artists are seldom fully satisfied with their own work, and there is something to be said for what was.

At other times, my affection for the subject clouded my artistic judgment. There are photographs I would love to have included in this volume and people who actually deserved more pages. But, with a critical editor’s eye, I could see that the images did not meet my standards. During this lengthy process, I realized that there are so many people whom I would love to reshoot!! This retrospective is a collection of primarily unpublished work documenting my fifty years in the motion picture business photographing an eclectic range of personalities. Although portraiture has and continues to be my passion, it is my personal work in the realm of the figure study that most often motivates me—the chance to step back and incorporate light and shadow with the human form, to create imagery that encompasses both ends of the spectrum in its entirety. It is the challenge of connecting the two to make a complete vision that balances my commercial work.

I learned so much from going back over everything and seeing many photographs that I barely remember shooting. I mentioned this to Elton John the other day and he told me the same thing. Sometimes he didn’t remember writing some of his music. Only the songs he’s currently working on are fresh in his mind, and that’s also true with my own photography. Recognizing that some of my most significant images were not ones that I had intentionally set up but were, instead, those moments in between when something spontaneous happened. Allowing things to unfold in a natural manner—this is where the magic often happens.

I also realize that part of the inherent beauty of film is its total lack of precision and its random nature. In today’s world of a quest for perfection, we have lost the true spontaneity and beauty of the art itself—the image. Going back through the archives from fifty years of work has amounted to taking a refresher course in analog photography. That has been interesting, but what’s touching is that again and again I recognized my good fortune. I have had friends. I have had assistants. I have had mentors. I have had great clients. I have had brave subjects—all of them have cared and put their trust in me.

This has been a humbling and enlightening journey, and one that has made me so glad I asked to borrow my friend’s Pentax back in 1968.